Of the many lessons learned from living in Italy, probably most important one was about persistence. Keep phoning that client for those late payments. Keep your elbows sharp to survive the Tuesday market scrum with your produce intact. Keep smiling, with that earnest, uncool American wattage until the regulars at the downstairs cafe smile back.

So pestering the conference organizers of European Forum on Disaster Risk Reduction (EFDRR) for an invite felt a bit like sliding back into my life as a freelance journalist in Milan. I was in Italy when the Genoa bridge collasped — extending the trip after talking about Resiliency Maps at the OpenStreetMap conference — and in the aftermath Angelo Borelli, who heads up the national Civil Protection agency, mentioned convening a bunch of experts in Rome in November to reduce future risks.

There were no details about this event in his comments. Nary a trace found on the internets. This was August, after all, when the whole country shutters for vacation – who could be expected to plan as far away as November? Before reaching out to journalist friends, I sailed off a request through a contact form on the Civil Protection website with about as much faith as you spend on a $1 scratcher. Who knows?

Six weeks later, when life in San Francisco had completely erased all thoughts of a conference in the Italian capital, someone answered my query with a link. The conference would pull together some 800 participants from 50 countries talking disaster risk reduction in Rome, organized by the United Nations Office for Risk Reduction (UNISDR). I launched into an email + phone + friend-of-friend offensive that eventually concluded in an invite — five days before the event. Just like old times!

Here are my main takeaways

The idea of resiliency first is gaining important momentum. If you’re not up to speed on the UN lingo (and, honestly, I’m still Googling furiously myself), the Sendai Framework, launched in 2015, serves as the scaffolding for this shift in mindset, planning, projects and funding.

It’s a 15-year campaign with four priorities:

- Understanding disaster risk

- Strengthening disaster risk management

- Investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience

- Enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response with the goal of “build back better”

There are seven targets – reduce global mortality, people affected by disasters, economic losses, damage to infrastructure and disruption of basic services while increasing countries with disaster reduction strategies, international cooperation and access to multi-hazard early warning systems.

The downside to Sendai — named after the tsunami-swept town in Japan where it was signed — keep in mind that it is a voluntary rather than binding agreement.

On the bright side, over 4,000 cities worldwide have signed up to the My City is Getting Ready initiative, which brings these goals down to a more workable level.

A few thoughts on the conference itself – from the content to the coffee.

Panel sessions? Where good conferences go to die

Their toxicity (or at least soporific power) multiplies by a factor of five with more than three people. The only time they work? When you have experts presenting different aspects of the same project or folks debating one very narrow topic or issue with clear, specific points of view. (See this post on the ResCult project.)

One session — 90 minutes long! After a pasta lunch! — featured a really sharp government official talking about chemical hazards and cyber attacks, an entrepreneur promoting his emergency awareness app, an insurance expert and a representative of an umbrella organization for civil society groups. The only person who really fit the topic (“Understanding Man-Made and Technological Risks”) was the first speaker, with an assist or two from the insurance expert.

Every single session was a panel. A panel decided by committee that didn’t have enough details nailed down in time for anything but the most general description in the program. None of the participants names made it into print. Details were stored in the interactive question platform — where the lights went off as soon as the event was over.

Less pomp, more rattle

Oil and water don’t mix – but shake them and you’ll make a decent vinaigrette. In the forest of technical terms, sub-governmental agencies and acronyms that make up the disaster reduction arena, the Resiliency Maps project is what you’d call civil society. Regular folks, the “community,” not employed by a government or NGO. So strictly not one of the principal actors in this conference. Still, I was delighted they’d accepted my application and looked forward to exchanging ideas.

However, some of the most obvious in vitees didn’t seem to have much direction. One government official’s sole contribution was to talk about a single pamphlet. A pamphlet that offered a very abbreviated overview of the obvious advice (keep water and food stores, find shelter). The most interesting thing about it was the title – what to do in the event of a disaster or war — curious since the country in question hasn’t faced conflict on home soil since the 1800s. (Upon questioning, it turns out the higher-ups insisted on that title.)

vitees didn’t seem to have much direction. One government official’s sole contribution was to talk about a single pamphlet. A pamphlet that offered a very abbreviated overview of the obvious advice (keep water and food stores, find shelter). The most interesting thing about it was the title – what to do in the event of a disaster or war — curious since the country in question hasn’t faced conflict on home soil since the 1800s. (Upon questioning, it turns out the higher-ups insisted on that title.)

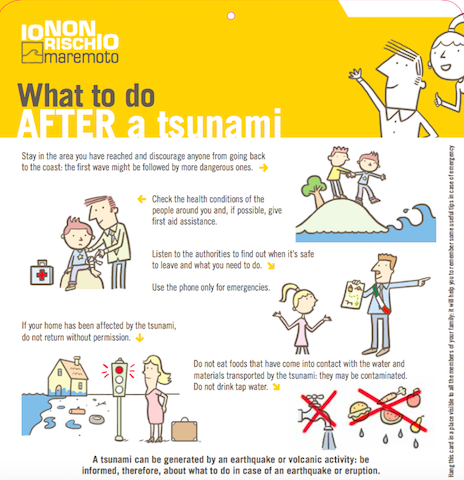

This very basic brochure stood in stark contrast to the Italian Civil Protection’s booth at the event showcasing materials they’d developed for the national market (and produced in English, too) called “I don’t take risks” for awareness and protection against earthquakes, floods and tsunamis. This was decidedly more detailed and useful, and instead of being a one-time mail deal, the campaign is still traveling around Italy and featured in “tweet storms.”

Over a coffee break — these provided serious fuel in the form of limitless espresso shots plus trays and trays and trays of pretty, bite-sized pastries — I cornered the chemical hazards expert and asked her take on the conference. “It’s nice to be here in Rome — but this is all a bit too abstract for me. I was hoping there would be more things I could take back home and act on.” Ditto. She mentioned that of the most interesting conversations she’d had were with the Civil Protection employees and volunteers, distinguishable from UN grandees because many of them sported neon-trimmed jumpsuits.

The conference venue was an 80s box of a building housing the Confindustria in Rome’s EUR neighborhood, not an area I’d covered in previous explorations to the city. The mix of a workaday Italian suburb — cafes with outdoor seating still viable in November, squat newspaper kiosks, cars colonizing the sidewalks for parking — stands in contrast to the fascist-era architecture. Only now that iconic building dedicated to workers (seen in the cover image here) houses Fendi corporate headquarters.

A fitting setting for the conference, which featured both lengthy opening and closing ceremonies with a torrent of officialese in two languages. When the Italian prime minister Giuseppe Conte and Mami Mitzutori, head of the UNISDR, finally stood to “open” the proceedings by halfheartedly hitting a gavel on a wooden block, my section of the auditorium erupted in a fit of giggles mixed with something bordering on sympathy.

While Conte — and his outsize security staff securing the perimeter of the entire city block — seemed a bit puffed up with his role, Mitzutori seemed to bear the pantomime with a quiet, if somewhat fatigued, dignity.

Later that day, she climbed into an earthquake simulator with Conte and some school kids. Watch her expression — the brunette on the right — and you’ll see what I mean.

Italy PM @GiuseppeConteIT and @HeadUNISDR Mami Mizutori experience 6.4 #earthquake in a simulation today @ #EFDRR2018 organized by @DPCgov ‘very realistic but at least we had a warning’ said Mizutori #SendaiFramework #ResilienceForAll pic.twitter.com/8aoWJREjI0

— UNISDR (@unisdr) November 22, 2018

Let’s keep talking about resiliency — and planning, funding, and doing something about it — with as little pomp and as much mixing as possible.