GENEVA — Floods, earthquakes and landslides are definitely scary. So how do you make preparing for a life-threatening disaster child’s play?

Just add Legos. A lot of them.

That’s what researchers in New Zealand found when experimenting with a program teaching grade schoolers to make asset and hazard maps by snapping together the colorful bricks.

“We all know that children are vulnerable and disproportionately affected when disasters strike, but it’s important to remember that they’re not passive victims,” says Loïc Le Dé, a senior lecturer in emergency and disaster management at the Auckland University of Technology. “They are resources — they’re aware who’s vulnerable in their communities, they know a lot about their environment, about resources and hazards.”

Kids, he says, are capable of conducting risk assessment and have the right as members of their communities to do so. They are rarely involved in those aspects of disaster risk reduction, however, mainly for lack of tools. The right tools can generate dialogue between children and outsiders — scientists, first responders, government — Le Dé said in a talk at the recent Global Platform on Disaster Risk Reduction.

That’s where Legos come in. The idea was to use a tool children are familiar with to give them a voice in designing community resilience. With financial backing from the national Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment and the Lego Foundation, the team set out to find the right school.

Brick by brick

Most of the 13 budding cartographers who worked on the Lego map, ages 10 to 12, are too young to remember the floods that swept through Maraekakaho in 2007. The local government and stakeholder groups were keen to build community resilience after floods in the area, about an hour inland on Hawke’s Bay in New Zealand’s North Island, prompted military evacuation of the school.

Even after pinpointing the right place, researchers were slightly lost: Just how many interlocking plastic bricks does it take to map an area to scale? They consulted Lego clubs but found no one had an answer.

Over four months and some twenty 90 minute-sessions (“quite a substantial process” Le Dé admits) they found out: it required 30,000 pieces of Lego.

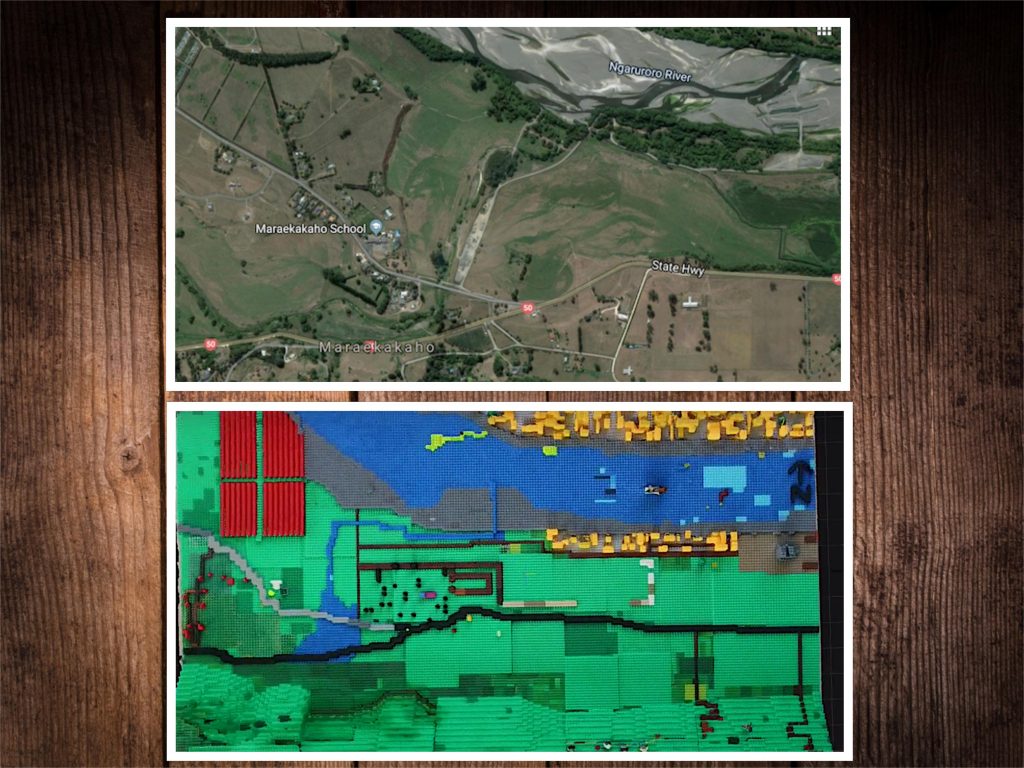

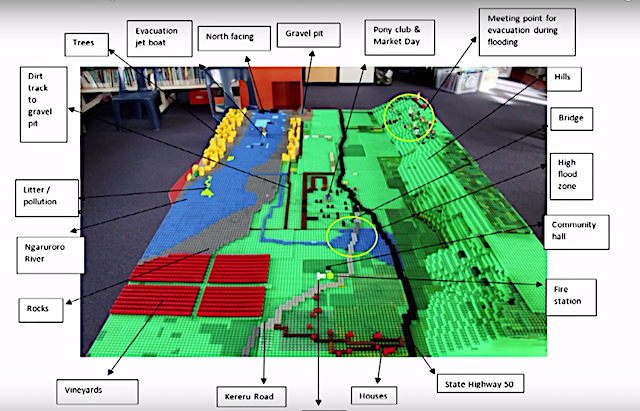

“We didn’t expect it, it’s very heavy!” Le Dé says. The map they built measures 190 cm x 114 cm covering a roughly two-by-three kilometer area. Far from being a colorful plaything, the map shows roads, buildings, rivers, elevation and the bricks are georeferenced.

“It means that it makes sense to outsiders when kids discuss information that’s on the map.”

DIY

And the Lego mappers definitely had ideas to contribute. In addition to marking dangerous areas on the Ngaruroro River, they came up with the idea of whisking people down waterways as a flood evacuation route. “These are things that teachers didn’t think about, these are things that we didn’t think about. You tend to dismiss kids or think they are not that creative or that knowledgeable about the area but actually they are.”

There are a few potential pitfalls to using Legos, Le Dé says. It’s time consuming and works best with a fairly narrow age range. (A companion project making Minecraft maps worked well with older students, they found.)

And, although you can’t walk across a living room in Western households without tripping over them, Legos aren’t common everywhere. Le Dé tells Resiliency Maps that he watched his own three-year-old pick them up in a snap but he’s not sure if the experience is transportable to other places, especially if towering heaps of those bricks need to travel.

What’s next? Le Dé tells Resiliency Maps that documentation for the project will soon be available online.

In the future, maybe more kids will be snapping together emergency plans.

This is part of our series reporting from the recent Global Platform on Disaster Risk Reduction. Stay tuned for more!

Cover photo // CC BY NC

One thought on “Teaching kids disaster prep with Lego maps”